In December 2018, Carrie Fuller wrote an article about teens’ sleeping habits during school. The key points from that article were that sleep is crucial for developing teens, teens were not getting enough sleep due to school start times, and that teens’ brains are wired on a biological clock. Well, it’s now May 2020, and school is not in session due to the COVID-19 virus. So, how have teens’ sleeping habits changed?

To reach optimal sleep, teens would have to sleep from 8-10 hours and follow their internal biological clock. There are two types of internal biological clock: sleep and wake homeostasis and circadian rhythm. Sleep and wake homeostasis is based on time awake and creates a balance in the body. Circadian rhythm suggests different periods of sleepiness and awakeness. Typical tired periods in teens are from 3-7 AM and 2-5 PM. Circadian rhythm is controlled by a group of cells that respond to light and dark.

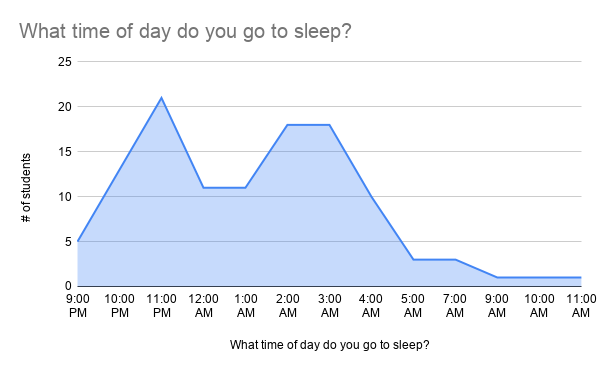

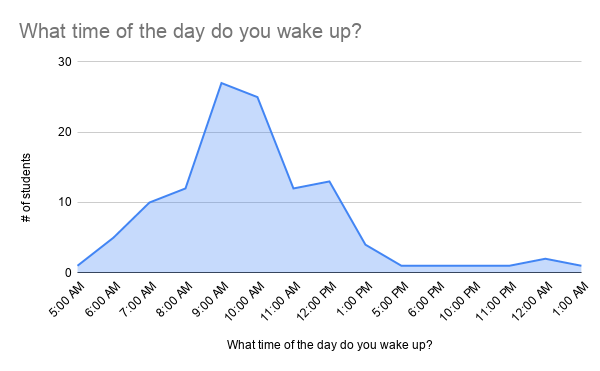

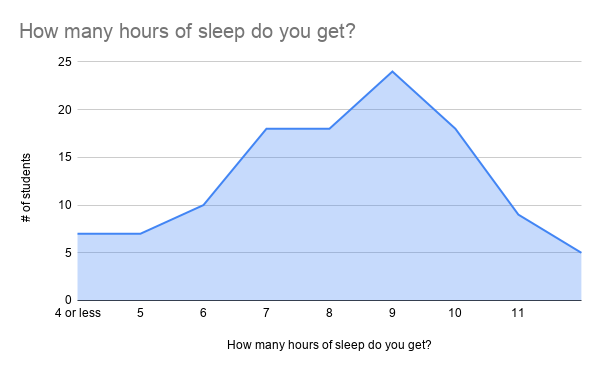

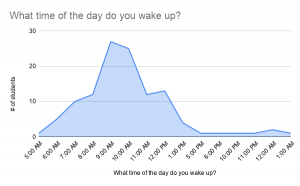

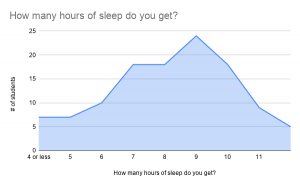

A recent survey was taken on current sleeping habits present in teens. The results (out of 116 students) are listed below:

The graph indicates that a lot of students are getting the sleep that they need, but just at unusual times. As of mid-May, it gets dark around 9 PM. However, many students are going to sleep around 11 PM-4 AM.

This can be explained in many ways. A possibility could be due to the lack of routine. Humans are creatures that run on routine. Get up, go to school, come home, do homework, go to sleep, repeat. Then the coronavirus surprisingly affected the world, including Pennsylvania, causing the school to shut down. This break of routine really surprises the human mind. Eventually, the human mind creates a new routine.

Another reason that teens are going to bed so late is electronic device usage. The blue light on many electronic devices, including TV, suppresses melatonin, making it harder to fall asleep. Even browsing the web, or seeing a certain post on social media can make the brain active. At night, keeping a mobile device within reaching distance can cause the chiming of the notifications to distract someone and keep them up. On average, people lose about an hour of sleep from that.

Phone addiction is also to blame. Over 2.5 billion people have smartphones, and they’re designed to keep us engaged. Apps simulate social interaction through notifications. For example, when Facebook notifies you that a friend is interested in an event that you’re interested in, that application is drawing you to its platform. This may sound surprising, but the “pull to refresh” gesture on many social media platforms provides a feeling similar to a slot machine. This makes it feel like the user is in control when in reality, the platform is in control. When Instagram notifies you of “new posts available,” that’s encouraging the user to stay on the app.

The million-dollar question is as follows: are the new sleep schedules of teens a problem? The answer is both yes and no. Since remote learning is on a student’s own schedule, one could say that it does not matter when teens go to sleep, as long as they’re getting enough of it. However, many of them might not be awake for teachers’ office hours, times where students can ask questions about assignments. Although, by the time this article is released, remote learning will be over very soon. Eventually, students will have to return to a normal sleep schedule when school goes back in session. This will have the same effect that going into quarantine had, the break of routine.

Call it a problem or not, most students are getting the amount of sleep that they need. In my opinion, that’s what matters most.

Sources: